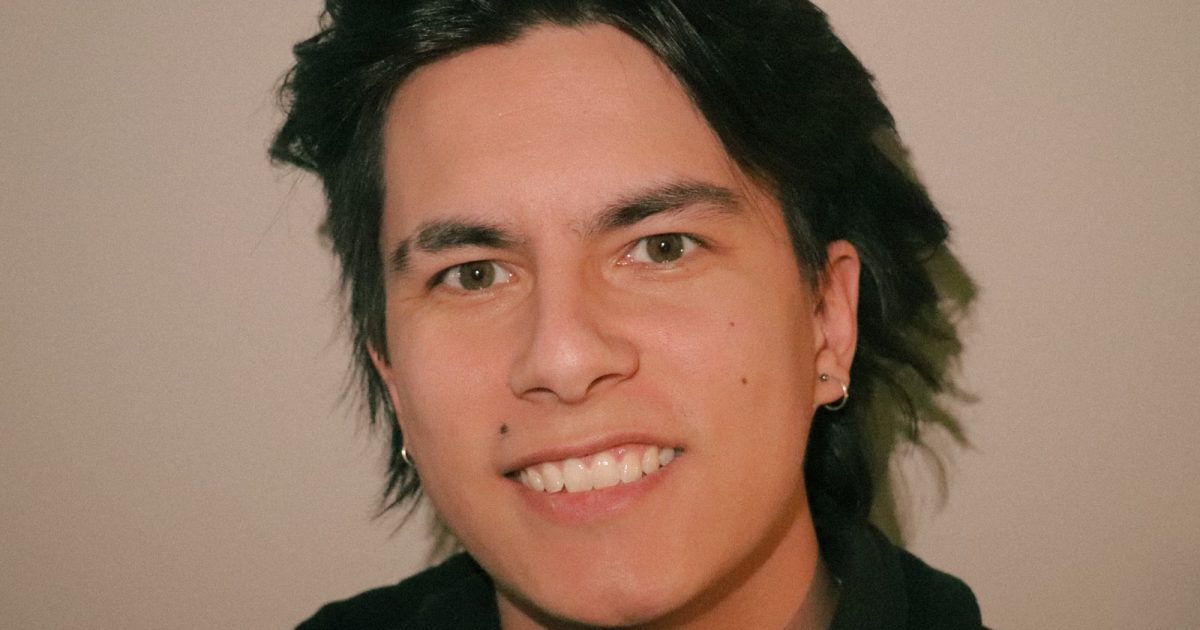

Growing up there were signs her mum called “Brianna-isms” that pointed to her having ADHD.

“I couldn’t regulate my emotions like a normal teenager, a normal kid, or I’d kind of have these adult ‘tantrums’ – if you want to call them that – where I just can’t regulate what’s going on with my emotions so I explode, and then I kind of come back down to normal thinking and I’ll be really embarrassed by it,” Tomasel tells the Herald.

“I’ve always wondered what that was about – just not being organised, always being anxious, having a million things going on inside my brain. It’s just never been quiet and I’ve always been like that, my entire life.”

Tomasel had never read about other women or girls with ADHD in research or in the media. “So I never, ever even thought that was me.”

Harwood says while she experienced anxiety growing up, her traits weren’t so obvious.

“The trigger for me was actually when my dad got diagnosed … I only got checked because we wanted to double check that my sister and I didn’t have it,” she explains.

“We knew she had it, like she was obviously ADHD based on stereotypes, you might say, but I actually never thought I had it until I started learning about it and found out that it can display really differently.”

While Harwood had a relatively short wait to get an assessment and diagnosis from a pyschiatrist – about four or five months – Tomasel was told by her GP last year that she was looking at a 10- to 12-month wait, so the radio host decided to talk to a psychologist in the meantime.

“I did an hour-long assessment with her and she talked to my mum as well and then read some of my old school reports … it was a really emotional experience. She was just super lovely and supportive.”

The next step, seeing a pyschiatrist, wasn’t so positive, she says – adding that she’s also tried medication for ADHD, which hasn’t worked for her so far.

“I might at some stage try a different one, but I think just having the answers is the main thing for me – and being able to understand myself and be kinder to myself, knowing that my brain is wired differently – that’s been the biggest thing.”

Both women say their friends and family weren’t greatly surprised by their diagnoses, though Tomasel reveals her parents took a moment to adjust to the news.

“There’s always that kind of parent guilt where they feel like they let you down, but it’s obviously not their fault. And then other people around me, especially the people closest to me like my partner, are like, ‘yeah, that [diagnosis] makes total sense’.”

Now, Tomasel compares having ADHD to “driving around a car that has all these problems and you not knowing about it, but you still have to try and get it from A to B”.

“If you know all the problems, you can get things fixed or help do things to make it easier to get from A to B, which has been super helpful for me, and also just understanding that ADHD comes with a lot of superpowers as well. That’s what I call them,” she explains.

“Because we’re so hyper-aware of everything, it makes us really empathetic people. We’re super creative. We can create or get something done in such a crazy way when we hyper-focus … there’s so many great things that come with it.”

Harwood notes the biggest challenge that comes with ADHD is living and working in an environment that’s not necessarily designed for neurodivergent people.

“It’s needing to be catered for and little accommodations … knowing that I actually work better in spurts as opposed to eight hours behind a desk.”

Tomasel adds that it was “emotionally draining” to go through the process of getting diagnosed, as well as come to terms with “the fact that you have been living in a world that’s kind of not structured for you, and you’ve struggled your way through”.

What you need to know about ADHD

Thanks to social media, it might seem there’s something of a trend to self-diagnose with ADHD – but as Harwood pointed out on air, we simply have more information about it now than ever before.

“It’s like back in the day left-handedness ‘didn’t exist’, really, but that’s only because people were being told ‘you can’t be left-handed’ – and all of a sudden, all of these left-handers appeared,” she told listeners.

“But it wasn’t because they just appeared. They were always there, they just were being suppressed.”

There are three types of ADHD: inattentive, hyperactive and combined. Both Harwood and Tomasel have been diagnosed with combined ADHD.

“Basically, the dopamine in your brain is the motivation receptor and that’s what makes you motivated to do things and people with ADHD lack it, so basic tasks become harder,” Harwood said on air, adding that it’s no surprise that people are looking for information online.

“It’s a privilege to get a diagnosis, because it’s not very accessible and it is quite expensive.”

Last year, paediatrician and child psychiatrist Dr Hiran Thabrew told the Herald evidence shows females are more likely to have undiagnosed ADHD.

They are also more likely to be diagnosed later in life, and “may be more likely” to be incorrectly diagnosed with a different neurodevelopmental or mental health disorder.

“While more research is needed in this area, one reason may be how symptoms present. Boys are more likely to show signs of hyperactivity and impulsivity, whereas we’re often seeing girls present with inattention as the most dominant symptom,” he said.

“We also often see more masking and internalisation of symptoms in girls, which can make it harder to identify.”

For more information about ADHD, and support resources, visit adhd.org.nz