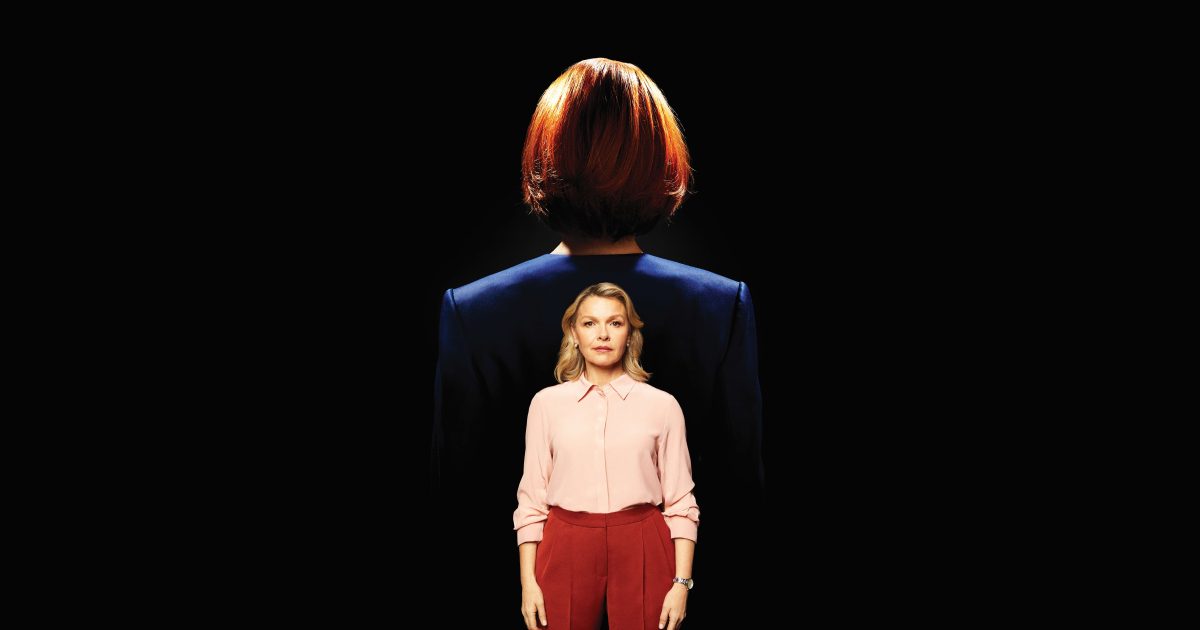

Palliative care veterinarian Dr Ashlee Flesser and her (perfectly healthy) pet cat. Photo: Supplied.

Canberran Dr Ashlee Flesser is one of a small number of Australian vets to buck what she says is a long-time trend of Australian veterinary care being behind human medicine.

The palliative care veterinarian works exclusively with geriatric animals or animals with terminal diagnoses at Sunset Vets dedicated palliative and end-of-life care service.

Dr Ashlee is following in the footsteps of Sunset Vets founder Dr Jackie Campbell, who less than a decade ago became Australia’s first certified palliative care veterinarian.

Both women hold a special US-based certification from the International Association for Animal Hospice and Palliative Care in addition to their veterinary qualifications.

“There’s no equivalent certification in Australia,” Dr Ashlee explains. “I think there’s probably only a handful of us [in Australia] that have done the certification.”

But the self-described “lady no one really looks forward to meeting” says there are a lot of benefits in-home palliative care can offer to much-loved pets.

“It’s a very holistic approach, compared with just identifying a particular disease process and then dealing with that disease,” Dr Ashlee says.

“On average, I spend probably an hour to two hours with palliative patients at the very first visit. That seems like a lot of time, but … at the end of that visit, we come up with a plan to assess not just a particular disease that might be happening but their comfort in general and any other geriatric medical conditions that pop up, like dementia and arthritis, which are quite common.”

The endpoint is discussed from the very first session, with the main goal of the treatment plan being not to extend the pet’s life but to improve the quality of life in their final months or years.

“Pets are quite good at hiding discomfort and pain so they don’t get targeted in the wild,” Dr Ashlee says. “So quite often, they don’t even tell us they’re sick until the end.”

Dr Ashlee typically spends eight to 12 months caring for pets in their late teens with chronic diseases through to younger pets diagnosed with conditions like terminal cancer.

It’s a very different model of care for the former general practice vet who would previously only have capacity to devote 10 to 15-minute appointments to pets at the end of their lives.

While forging these relationships with owners and their pets means Dr Ashlee sometimes ends her work days in tears, she says it’s a misconception that her job is “all doom and gloom”.

“It certainly is sad, don’t get me wrong, but in our consults, there are often a lot of laughs,” she says.

“We joke around and we share a cup of tea and we chat about things that aren’t death.”

Dr Ashlee recommends owners start the conversation about palliative care interventions before the point when euthanasia is imminent to manage expectations and do what’s best for their pet.

“It is something that I think a lot of people might put off doing or exploring until it is quite late in the piece,” she says. “Palliative care intervention is something that is okay to look at early.

“I think our general populace should perhaps work towards getting more used to having these conversations and to have that subject not be so hush-hush and kept under the rug.”