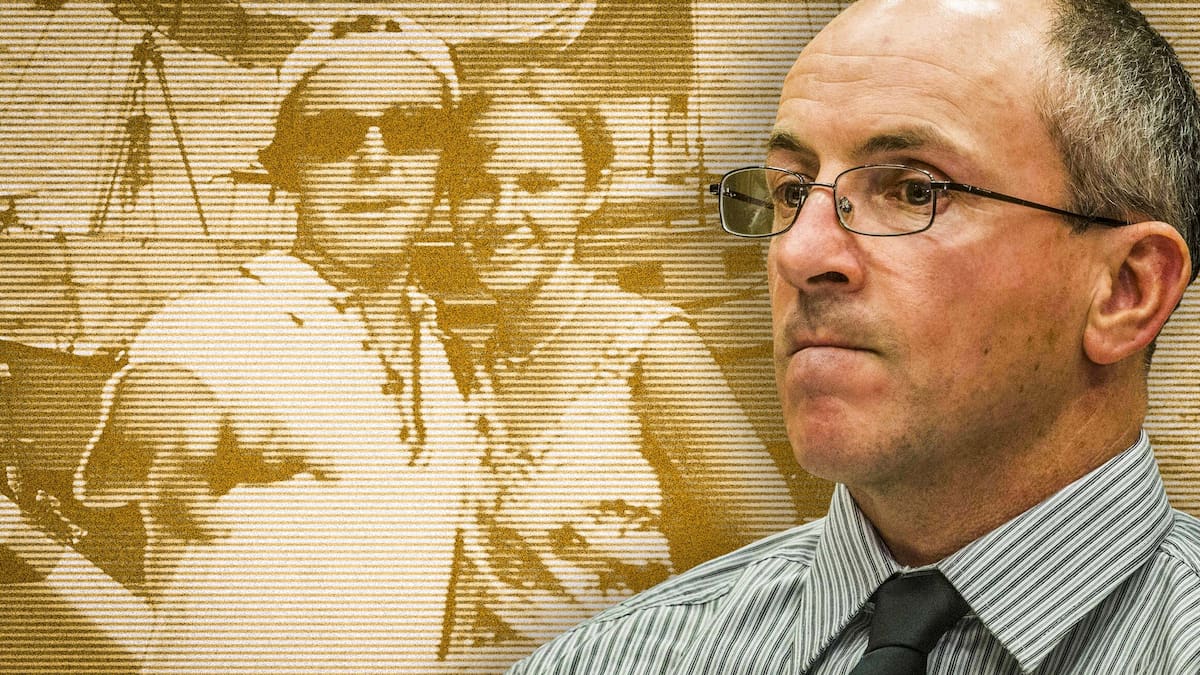

Scott Watson is seeking to overturn his convictions for the murders of Ben Smart and Olivia Hope. Composite photo / NZME

The forensic scientist who tested the hairs on a blanket from Scott Watson’s boat, has told a court she wasn’t surprised she didn’t initially find two blonde hairs linking to missing teen Olivia Hope when she first examined it.

The scientist was giving evidence at Watson’s Court of Appeal hearing in Wellington, where he’s seeking to overturn his convictions for the murders of Hope and her friend Ben Smart.

Hope, 17, and Smart, 21, were last seen getting out of a water taxi and onto a yacht moored in Endeavour Inlet in the Marlborough Sounds on New Year’s Day in 1998. Their bodies and possessions have never been found.

After they vanished two strands of hair – one 15cm long and the other 25cm – were purportedly found on a blanket taken from Watson’s boat, Blade.

The blanket was first examined in January 1998 but no hairs were found. In March of that year, after samples of Hope’s hairs were sent to the ESR laboratory, the blanket strands were tested again. This time two strands of blonde hair were found.

The Crown then successfully argued at Watson’s original trial that the hairs were linked to Hope.

Today, forensic scientist Susan Vintiner told the court she wasn’t surprised she didn’t find the blond hairs the first time she examined the blanket, given the short time she spent looking at the exhibit and it was difficult to see blond hairs in a bag containing 400 brown hairs that were also found on it.

There was also a cut in the bag holding the hair, but Vintiner told the court she would be speculating to say how the hole got there.

‘I could have been more transparent’

Watson’s lawyer Nick Chisnall KC questioned Vintiner about her evidence to the jury at Watson’s original murder trial in 1999 and whether she should have made more at the time of how the hair could have ended up on the blanket.

“No, I don’t accept that because I believe that when I was asked (transference) was a possibility by (crown prosecutor) Mr Davidson, I agreed with him, I said that yes it should be considered, the jury should consider this.”

She said if she was giving the evidence again she would have included the issue of secondary transfer (where a hair is transferred to an intermediary place and then onto another person) in her statement.

“It could have been more transparent, I accept that,” she said.

Vintiner accepted the evidence of another witness that it’s not possible to say how the hairs transferred on to Watson’s boat, Blade.

Earlier today another forensic scientist, Sean Doyle, raised concerns about the way the hair samples were dealt with.

Doyle wrote three reports for Watson’s defence team saying that Vintiner used her “personal preferences” when examining the hairs, rather than standard methods.

He told the court there was no record in the case file of what procedure Vintiner used when removing the hairs. He said what was recorded in the case file didn’t match what was in Vintiner’s affidavit about the methods she used.

“My expectation would be today that the procedure she used would actually be in the SOP (standard operating procedure).

“And because she’s using her personal judgment, I would expect a detailed record to be made and certainly recording what she actually did in terms of ‘I cut the bag open, I put the tweezers in and I pulled the hair out.”

Crown lawyer Robin McCoubrey suggested there was nothing wrong with a scientist using their individual preference, as Vintiner did in this case.

Doyle questioned whether this was best practice, although he conceded the world was a very different place in 1998.

Under cross-examination, Doyle conceded the issues of contamination and transference of the hairs in the laboratory was dealt with at the original trial, with Justice Heron directing the jury it was a question for them to consider.

He also accepted that at the original trial, Watson had four experts at his disposal to challenge the evidence as it was presented then.

The Crown says the accuracy of the DNA test for the longer hair means there is strong support it came from Hope. But the DNA evidence for the shorter hair suggests it came from Hope or a maternal relative.

Paige McElhinney, a forensic scientist, told the court most hair transfers were indirect, explaining that a direct transfer would be effectively pulling a hair from your head.

Asked by McCoubrey how Hope’s hair transferred onto Watson, if, as he’d claimed, they’d never met, McElhinney said they might have brushed past each other on the night of the party at the lodge.

Watson was convicted of double murder in September 1999 and sentenced to life imprisonment, with a minimum period of 17 years in jail. He has now spent 26 years behind bars, protesting his innocence.

The latest appeal is the result of a royal prerogative of mercy, applied for in 2017 and granted in 2020. The grounds for the appeal are two-fold:

- The reliability of DNA evidence, specifically hairs that were thought to belong to Hope and were recovered from Watson’s boat.

- Mistakes by the police in using a photo montage as a means of identifying Watson. The montage contained a new photo that showed Watson caught halfway through a blink. This gave the appearance of hooded eyes, a characteristic of the mystery man’s description.

Watson is not attending the Court of Appeal hearing which is before Justices Christine French, Patricia Courtney and Susan Thomas.

Tomorrow the court will hear from the final three witnesses before lawyers make their submissions.

Catherine Hutton is an Open Justice reporter based in Wellington. She has worked as a journalist for 20 years, including at the Waikato Times and RNZ. Most recently she was working as a media adviser at the Ministry of Justice.