Onstage Thursday night, Joel reminded the audience of the band’s accomplishments: “We were the first American full-fledged performance in the Soviet Union,” he said. “We played in front of the Colosseum in Rome for a half a million people. And the food was great,” he quipped. “But out of all of them, this is the best.

“The band loves it; the crew loves it,” he continued. “We’ll come back.”

The Piano Man and his adoring audience.Credit: Getty Images

The show included an appearance by Jimmy Fallon, who feted a beaming Joel as a banner marking the 150th concert was hoisted above the stage. “You’ve given us all great memories of being here,” he said. “We’re actually getting to watch you live a memory.”

A surprise performer, Guns N’ Roses frontman Axl Rose, strutted in a black blazer twinkling with sequins while singing his band’s version of Live and Let Die and a cover of AC/DC’s Highway to Hell; he returned for the finale, joining Joel on You May Be Right.

Joel said he first met Rose years ago in Los Angeles at a club on the Sunset Strip, where the tattooed hard-rock lifer quizzed him about his catalogue. “He was dying to talk to me,” Joel said, raising his eyebrows to underscore his surprise. While Rose was inquiring about Joel’s hard-luck tune Captain Jack, a lineup of women awaited Rose’s attention. “They’re leaning over in front of him, like, displaying their goods,” Joel remembered. “And I’m like, why are you talking to me?”

Previous guests have included Miley Cyrus (“She belted out New York State of Mind like Barbra Streisand,” he marvelled), Paul Simon, Bruce Springsteen, Elvis Costello, Brian Johnson of AC/DC and Olivia Rodrigo, who played both Uptown Girl and her own song that name-checks it, Deja Vu.

Loading

John Mayer, who guested in 2015 on the heart-string-tugger This Is the Time, said Joel’s magic comes from staying his own course and making decisions that run counter to conventional pop wisdom. “Most people try to make big rooms big,” he said. “He turned the Garden into a club,” achieving “the purest direct connection between the music and the audience. That’s the ultimate.”

The idea for the residency was sparked at a dinner in Turks and Caicos attended by Arfa and Jay Marciano, who was then the president of Madison Square Garden (he now heads up the touring giant AEG). Joel had proved to be a huge local draw, and his appearance at the 12-12-12 benefit for Hurricane Sandy relief was the night’s buzziest moment. Would he be interested in becoming a Garden franchise like the New York Knicks?

“I didn’t really know what the whole thing encompassed,” Joel admitted. “I thought, OK, a residency. So we’ll play, you know, like, a couple of gigs in a row.” (The scale of the setup sank in during the news conference to announce it.)

“I never imagined playing this late in life, anywhere,” he said. “I thought you had to go to the retirement home in rock ‘n’ roll.”

Instead, a crop of major acts older than 75 — Joel’s recent tour mate Stevie Nicks, the Rolling Stones, Eagles, Neil Young, Willie Nelson, Bob Dylan — are thriving on the road. Joel’s unvarnished stage show has been drawing a multi-generational audience that sings along to every word. “It turns out,” said Mayer, who’s been playing with septuagenarian members of Dead & Company, “a good song is not debatable through the years.”

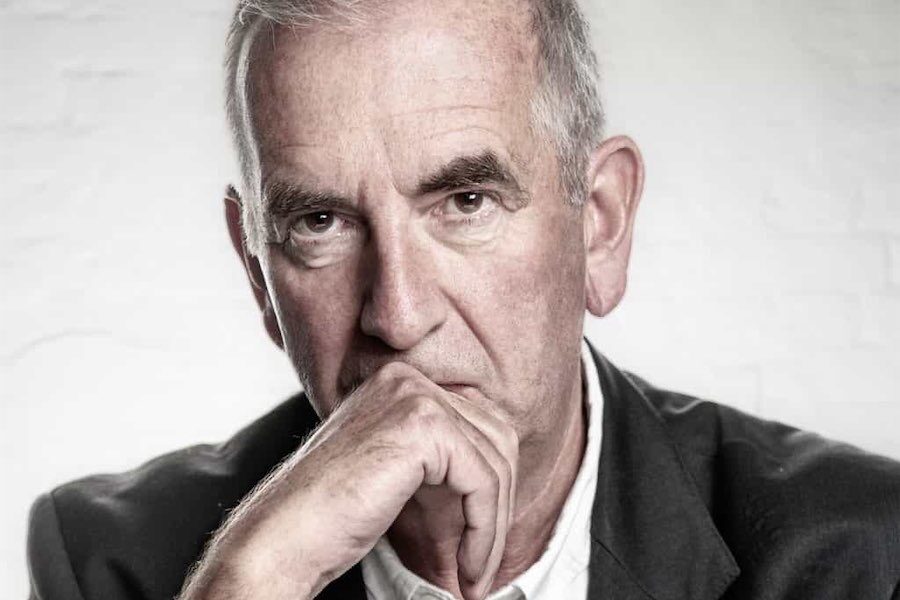

Billy Joel at a 2018 press conference honouring his 100th Lifetime Performance at Madison Square Garden. Credit: Getty Images

Arfa, the agent, said his client of nearly five decades is bigger than ever, from a touring perspective: “What’s really happened in the last 10 years is Billy has evolved into a stadium artist.” When you accomplish that kind of feat when you’re younger, “that’s one kind of a feeling,” he said. “It’s a different euphoria when you’re older.”

The time that’s elapsed between age 65 and 75 has brought new challenges. “The way you hear is different. The way you sing is different,” Joel said. He uses more falsetto — he called it “throwing junk pitches,” like knuckleballs instead of fastballs. “I’m not crying,” he announced onstage in May, explaining a teary eye. “A lot of weird [expletive] happens when you’re 75.”

The residency has spanned significant changes in Joel’s personal life, too. He married for the fourth time. He stopped drinking. He started the run with one daughter; now he has three, and the Garden is “another place for them to be with dad,” he said of his two youngest. “That’s their home. They have a playroom backstage.” They briefly stole the spotlight during My Life on Thursday, as Remy, 6, rested atop his piano and Della, 8, acted out the lyrics at the front of the stage. “How do you follow that?” Joel only half joked.

The Garden has been a base for his musical family members, too, many of whom have been with him for decades, including saxophonist Mark Rivera and Crystal Taliefero, the powerhouse percussionist, sax player and singer.

Loading

“I feel blessed that Billy’s been able to allow us to be our true selves and express ourselves,” she said in a phone interview from the Four Seasons, where the band was staying for a recent show in Denver. (“Thanks, Billy!” she said with a laugh.) “There’s so much energy in that room, even before the people are in there,” she added, calling the Garden “a comfort zone.” She’s had the same dressing room there for 35 years with Joel; Muhammad Ali came to visit after one show “and told me, ‘You’re doing a great service.‘”

Joel’s career hasn’t always been a steady climb. His public struggles with sobriety and high-profile breakups landed him in the gossip pages. In 1989, he sued his ex-manager for $US90 million, alleging fraud. Critics weren’t always warm to his poppy style, which draws inspiration from early rock, doo-wop and the American songbook. Joel is also his own toughest critic: “I saw Zeppelin there. I saw Elton. I saw Bruce. All the big shots,” he said of the Garden. “And when I’m up onstage, it’s still a little bit bewildering. Like, what am I doing here? I know who I am. Why are all these people coming to see me?”

But the songwriter, who worked as a music critic himself for $25 an article in the ’60s — briefly, “I don’t have the stomach for it” — maintains no grudges: “I’ve been very, very lucky,” he said, comparing hanging on to the past to a malignant tumour. “I was moaning and bitching early on when I would get bad reviews, and now I realise, oh, they did me a favour. My career didn’t peak too early.”

At a soundcheck four hours before showtime, a still-relaxed Joel refreshed himself on a few tracks, kibitzed with the band and confirmed whether he could hit one of his most famous high notes, in An Innocent Man. He nailed it, eliciting a “Yeah, baby!” from Taliefero.

“The whole premise of being a musician was having fun,” he said a week ago. “I’m still having fun. I’m doing the same job I did when I was 15,” he added, “and what a great job.”